How to turn an RPG into a board game in 147 steps - part 2 (Non-linear Storytelling)

I was ruminating last week on the nature of reducing a tabletop RPG game master into a deck of cards, and I'd like to get back to that. Keep in mind, though, that it's a big undertaking. The game master isn't just responsible for generating the world in which the players inhabit, but also making the decisions of every living thing in that world outside of the players. It is best to tackle this problem one step at a time.

So how do you create a world that players can immerse themselves in and interact with in a board game? The main answer here is writing. Lots and lots of writing. Without a human being to act out every NPC players talk to and describe the random details of everything the players look at, the only thing you can fall back on is the written word - a convincing, well-crafted narrative that players can engage with.

This is a pretty tried and true solution, and there are many games that employ it well: Mice and Mystics, Descent, Betrayal at House on the Hill. Each one features scenarios which are set up with multiple paragraphs of narrative to help players better experience what is happening.

Of course, the level of effectiveness varies from player to player. Some players have little tolerance for reading so much text in preparation to play a board game. I find myself on the opposite end of the spectrum, however. In case you can't tell, my tolerance for language is very high, and I find Mice and Mystics, by far the most verbose of those games mentioned, to be by far the most effective.

In the end, though, you need something more than mere writing. You need something that makes the difference between reading a novel and reading a "Choose Your Own Adventure" book. Sure, novels are great, but I've always preferred the "Choose Your Own Adventure" stories.

Players need choices.

I don't want to harp too much on other story games, because I love Mice and Mystics and Descent, but they always felt too "on the rails" for me. Don't get me wrong - there are choices in the game, but they never felt that meaningful. In the end, everything always shakes out the same way (unless you lost). I never felt like I was free to explore the world that the game had created.

The solution is simple...and also complicated. You structure the scenarios like a "Choose Your Own Adventure" instead of a linear novel. The concept is simple, but the implementation is rather difficult. Even after plotting how the various story lines would branch and intersect, each branch of the path means more and more scenarios to design and balance. And each one needs to feel fresh and distinct from all the others.

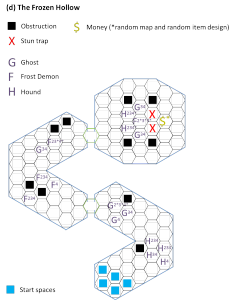

And then all of the information on all the scenarios - the setup, the enemies, the treasure, the victory conditions, the flavor writing, the choices and how to go from one scenario to the next - needs to get wrapped up perfectly and succinctly into some sort of manageable booklet the players can reference. As I said, it's complicated.

I was ruminating last week on the nature of reducing a tabletop RPG game master into a deck of cards, and I'd like to get back to that. Keep in mind, though, that it's a big undertaking. The game master isn't just responsible for generating the world in which the players inhabit, but also making the decisions of every living thing in that world outside of the players. It is best to tackle this problem one step at a time.

So how do you create a world that players can immerse themselves in and interact with in a board game? The main answer here is writing. Lots and lots of writing. Without a human being to act out every NPC players talk to and describe the random details of everything the players look at, the only thing you can fall back on is the written word - a convincing, well-crafted narrative that players can engage with.

This is a pretty tried and true solution, and there are many games that employ it well: Mice and Mystics, Descent, Betrayal at House on the Hill. Each one features scenarios which are set up with multiple paragraphs of narrative to help players better experience what is happening.

Of course, the level of effectiveness varies from player to player. Some players have little tolerance for reading so much text in preparation to play a board game. I find myself on the opposite end of the spectrum, however. In case you can't tell, my tolerance for language is very high, and I find Mice and Mystics, by far the most verbose of those games mentioned, to be by far the most effective.

In the end, though, you need something more than mere writing. You need something that makes the difference between reading a novel and reading a "Choose Your Own Adventure" book. Sure, novels are great, but I've always preferred the "Choose Your Own Adventure" stories.

Players need choices.

I don't want to harp too much on other story games, because I love Mice and Mystics and Descent, but they always felt too "on the rails" for me. Don't get me wrong - there are choices in the game, but they never felt that meaningful. In the end, everything always shakes out the same way (unless you lost). I never felt like I was free to explore the world that the game had created.

The solution is simple...and also complicated. You structure the scenarios like a "Choose Your Own Adventure" instead of a linear novel. The concept is simple, but the implementation is rather difficult. Even after plotting how the various story lines would branch and intersect, each branch of the path means more and more scenarios to design and balance. And each one needs to feel fresh and distinct from all the others.

And then all of the information on all the scenarios - the setup, the enemies, the treasure, the victory conditions, the flavor writing, the choices and how to go from one scenario to the next - needs to get wrapped up perfectly and succinctly into some sort of manageable booklet the players can reference. As I said, it's complicated.

And this is really the main thing I'm working on at the moment - developing scenarios and testing them for enjoyability and balance. But, still, it can't just be a matter of, "Okay, you get to the end of this scenario, make a choice and then go to this scenario based on that choice." It gives players choices, but it still puts them on rails, bouncing from point to point to point without any real freedom.

Like any good RPG, the game needs side missions. More than that, I feel it should allow for multiple groups of players to interact with the same game space.

Let me attempt to explain:

You crack open the game box with your group of gaming friends, read the rules and choose your characters. You look at the world map and see a small town - let's call it "Haven" - surrounded by all manner of unexplored wilderness. You crack open the first page of the scenario booklet and it gives you your first mission: head into a bandit hideout to retrieve some documents stolen from a merchant. You've just unlocked your first dungeon - put a sticker on the world map. So you set up the first scenario and get into the game, but are immediately met with a choice: chase the bandit into the catacombs below the hideout or loot the bandits' treasure room and call it a day. That choice will unlock one of two new dungeons to explore, which will lead to new choices and even more dungeons. Eventually, you'll also begin to unlock optional side dungeons which don't serve the story, but may offer valuable loot or the change to fulfill a player's ultimate career goal (more on that in a later post).

Each dungeon you discover is a new sticker on the map that is now available for anyone to go and explore for more loot and experience. And if you break out the game at your local game night for a one-off hack-and-slash mission, you can go into any explored dungeon not to advance the story, but just to have fun. And if you wanted to start a different campaign with a new group, you could do that too, exploring random dungeons, continuing the story of the original group, or investigating a dangling plot thread that the previous group neglected. The world is your oyster and it continually grows and expands the more you play in it.

There's obviously more logistics to it than the explanation lets on, but hopefully that sounded reasonably awesome. It does to me, anyway.

So now we've got a scenario booklet that lets players pick up and explore the game at their leisure in a variety of ways. Freedom and choice. Awesome.

But as I said at the top, the game master does more than just create the world. Next week I'll start discussing the actual mechanics of the game and finally get to all those decks of cards.

And this is really the main thing I'm working on at the moment - developing scenarios and testing them for enjoyability and balance. But, still, it can't just be a matter of, "Okay, you get to the end of this scenario, make a choice and then go to this scenario based on that choice." It gives players choices, but it still puts them on rails, bouncing from point to point to point without any real freedom.

Like any good RPG, the game needs side missions. More than that, I feel it should allow for multiple groups of players to interact with the same game space.

Let me attempt to explain:

You crack open the game box with your group of gaming friends, read the rules and choose your characters. You look at the world map and see a small town - let's call it "Haven" - surrounded by all manner of unexplored wilderness. You crack open the first page of the scenario booklet and it gives you your first mission: head into a bandit hideout to retrieve some documents stolen from a merchant. You've just unlocked your first dungeon - put a sticker on the world map. So you set up the first scenario and get into the game, but are immediately met with a choice: chase the bandit into the catacombs below the hideout or loot the bandits' treasure room and call it a day. That choice will unlock one of two new dungeons to explore, which will lead to new choices and even more dungeons. Eventually, you'll also begin to unlock optional side dungeons which don't serve the story, but may offer valuable loot or the change to fulfill a player's ultimate career goal (more on that in a later post).

Each dungeon you discover is a new sticker on the map that is now available for anyone to go and explore for more loot and experience. And if you break out the game at your local game night for a one-off hack-and-slash mission, you can go into any explored dungeon not to advance the story, but just to have fun. And if you wanted to start a different campaign with a new group, you could do that too, exploring random dungeons, continuing the story of the original group, or investigating a dangling plot thread that the previous group neglected. The world is your oyster and it continually grows and expands the more you play in it.

There's obviously more logistics to it than the explanation lets on, but hopefully that sounded reasonably awesome. It does to me, anyway.

So now we've got a scenario booklet that lets players pick up and explore the game at their leisure in a variety of ways. Freedom and choice. Awesome.

But as I said at the top, the game master does more than just create the world. Next week I'll start discussing the actual mechanics of the game and finally get to all those decks of cards.

Leave a comment

Comments will be approved before showing up.